/

Jan 13, 2026

Understanding AI value starts with GDPval

GDPval is OpenAI’s economic framework for measuring AI value: does AI reduce the cost of producing professional work experts accept? Learn why most AI initiatives fail economically, why gains are non-linear, and how to measure task-level cost advantage that enables real ROI.

/

AUTHOR

Tristen van Vliet

GDPval is an economic evaluation framework developed by OpenAI to assess whether AI systems create measurable business value. Instead of asking how intelligent a model appears, GDPval asks a more practical question: does AI reduce the cost of producing work that professionals would accept? By focusing on real workflows, expert judgment, and economic outcomes, GDPval offers organizations a concrete way to reason about AI value.

Stepping into 2026, this is how we finally know whether AI works.

According to MIT’s State of AI in Business 2025 report, 95% of enterprise AI initiatives deliver zero measurable return. Despite tens of billions in investment, most projects stall in pilots, fail to scale, or never show P&L impact (Challapally et al., 2025).

This is not a model quality problem.

It is a measurement problem.

Most organizations still evaluate AI in the wrong way. Adoption metrics, abstract benchmarks, and isolated productivity anecdotes dominate decision making. What is missing is a clear answer to a simple economic question: does this system reduce the cost of producing acceptable work?

GDPval is one of the first serious attempts to answer that question.

Why most AI projects fail economically

MIT’s research shows a consistent pattern. AI tools are widely explored, frequently piloted, and rarely deployed at scale. More than 80% of organizations experiment with generative AI, yet only about 5% extract meaningful value. The failure is not driven by regulation or lack of interest, but by brittle workflows and an inability to connect AI performance to business outcomes (Challapally et al., 2025).

In short, organizations do not know how to measure whether AI is working, and therefore cannot justify scaling it.

This is where GDPval reframes the problem.

From intelligence to economically valuable output

GDPval does not ask whether AI is intelligent. It asks whether AI can produce real professional deliverables that experts would actually accept (Patwardhan et al., 2025).

Tasks are drawn from real work performed by industry professionals with an average of fourteen years of experience, across forty four occupations and nine sectors representing more than three trillion dollars in annual wages. Outputs are evaluated through pairwise expert judgment. Would a professional prefer the AI generated deliverable, or the human one?

This approach aligns evaluation with how organizations actually operate. Business value is created through documents, analyses, and decisions, not through test questions.

The counterintuitive economic result

The headline result is striking. Frontier AI models now produce expert acceptable output in roughly 50% of cases, while generating first pass deliverables 50 to 300 times faster than human experts.

On its own, a fifty percent acceptance rate may sound insufficient. Economically, it is transformative.

GDPval explicitly models the workflow most enterprises already use:

AI produces an initial output

An expert reviews it

Only if the output fails does the expert redo the task from scratch

The expected cost can be written as:

Expected cost (EC) = Model cost (MC) + Review cost (RC) + (1 − w) × Human cost (HC)

Here, w is not accuracy. It is the probability that the AI output is accepted.

This framing explains why so many AI pilots fail. They are rarely evaluated on whether they reduce the expected cost of producing acceptable work.

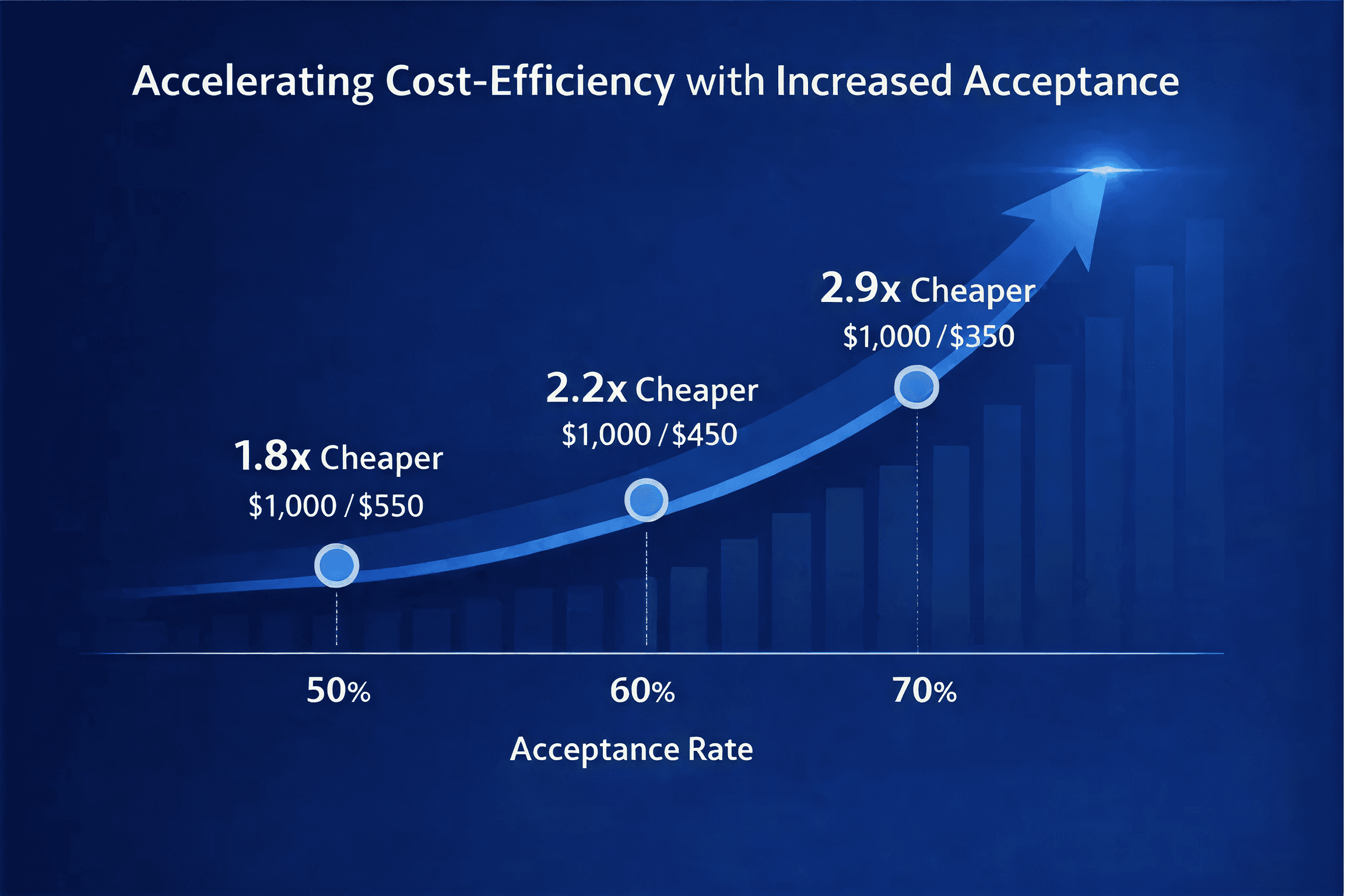

Why improvement is not linear

Crucially, the economics are not linear.

Acceptance determines how often an organization must fall back on the most expensive path, full human execution. Every reduction in that probability operates through a ratio effect on economic return, not through a simple additive gain.

AI speed remains constant. Review costs remain relatively fixed. What changes is how often the organization pays the full human cost. As acceptance rises from fifty to sixty or seventy percent, economic advantage increases faster than the improvement itself.

This is why AI value emerges before perfection, and why many organizations misjudge its impact.

Bridging the gap MIT identifies

MIT’s report describes a GenAI divide. A small minority of organizations capture real value, while the majority remain stuck in pilots with no measurable impact. The divide is driven by approach, not ambition.

What separates the two sides is not belief in AI, but economic clarity.

At the task level, the key signal is simple: how much cheaper does producing acceptable work become when AI is introduced? GDPval makes this explicit by comparing the expected AI-assisted cost of a task to the cost of full human execution. The resulting cost ratio, HC / EC, shows whether AI is economically dominant for a given unit of work.

This ratio does not represent full ROI. It shows something more fundamental: whether AI creates structural cost advantage at the task level. So GDPval does not replace financial ROI analysis; it enables it. Only when that per-task efficiency exists does it make sense to scale usage, accumulate volume, and compare aggregated savings to fixed program costs.

This distinction explains MIT’s findings. Many organizations invest in AI without first establishing task-level economic advantage. As a result, pilots never translate into durable return. GDPval provides a way to identify where that advantage already exists, and where long-term ROI can realistically emerge as usage scales.

Measuring what markets actually reward

Stepping into 2026, the AI conversation is shifting. The question is no longer whether models can reason, write, or summarize. It is whether organizations can systematically convert probabilistic AI output into reliable economic value.

MIT shows how widespread failure looks.

GDPval shows how to measure it, and therefore how to avoid it.

Across industries representing trillions in wages, the tools to cross that divide are visible. The remaining challenge is not intelligence, but economics.

At Subduxion, we translate these dynamics into clear, practical insights for organizations navigating AI adoption. If you want to understand the economic impact AI could have in your specific context, we are happy to explore that together.

A simple example to make this concrete

Consider a single, repeatable professional task.

A human expert completing the task from scratch costs $1,000.

An AI system can generate a first draft for $10, which an expert can review for $40. Together, the AI-assisted path has a fixed upfront cost of $50 per task.

If the AI output is not acceptable, the expert still has to complete the full task.

The expected cost of producing an acceptable outcome can therefore be written as:

Expected cost (EC) = $50 + (1 − w) × $1,000

where w is the probability that the AI output is accepted.

If AI output is accepted 50% of the time, the expected cost is:

$50 + 0.50 × $1,000 = $550

At 60% acceptance, the expected cost becomes:

$50 + 0.40 × $1,000 = $450

At 70% acceptance, it drops further to:

$50 + 0.30 × $1,000 = $350

At the task level, the relevant signal is the cost ratio between human-only execution and AI-assisted execution:

Task-level cost ratio = HC / EC

This gives:

50% acceptance → $1,000 / $550 ≈ 1.8× cheaper

60% acceptance → $1,000 / $450 ≈ 2.2× cheaper

70% acceptance → $1,000 / $350 ≈ 2.9× cheaper

Each increase in acceptance improves quality by the same amount, but the economic advantage accelerates. The reason is straightforward: the most expensive path, full human execution, is avoided more often, while AI speed and review costs remain constant.

This is why AI economics are non-linear. Acceptance determines how often the most expensive path is taken, and every reduction in that probability increases the cost-efficiency ratio faster than the acceptance rate itself. True ROI emerges later, when this per-task efficiency is scaled across volume and compared to fixed program costs.

References

Challapally, A., Pease, C., Raskar, R., & Chari, P. (2025). The GenAI divide: State of AI in business 2025. MIT NANDA.

Patwardhan, T., Dias, R., Proehl, E., Kim, G., Wang, M., Watkins, O., Posada Fishman, S., Aljubeh, M., Thacker, P., Fauconnet, L., Kim, N. S., Chao, P., Miserendino, S., Chabot, G., Li, D., Sharman, M., Barr, A., Glaese, A., & Tworek, J. (2025). GDPval: Evaluating AI model performance on real world economically valuable tasks. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.04374